Inhabiting a language: Latin via the Direct Method

~ by Maria Overy ~

A most famous English philologist by the name of J. R. R. Tolkien, wrote, spoke, and imagined with a language of his own invention. For Tolkien, the invention of a language was a prerequisite for the creation of a world:

‘The invention of languages is the foundation. The ‘stories’ were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse.’ [Letter to the publishing company Houghton Mifflin Co., 30th June 1955].

I perceive there to be an analogy between Tolkien’s practice, and the learning of languages in an immersive setting. In the latter case there is no ‘invention’, for the language of study has been prescribed. Nevertheless, the classroom can still become a world, brought into being by the students inhabiting a foreign language.

I experience this happening in the classes in which I am enrolled as a student at the Polis Institute of Languages & Humanities in Jerusalem. I take classes in both Biblical Hebrew and Ancient Greek, the two original languages of the Bible. Not a word of English is spoken, and great pains are taken to use only vocabulary that has been hitherto encountered. I can apply the techniques I see modelled by my teachers to the immersive Latin classes I teach for Scholé.

Let me paint a picture of how this could possibly work by describing the classes. My Hebrew teacher, Eyal Nahum, has designed his own immersive Biblical Hebrew course which invites students to inhabit a world born out of Holy Scripture. Upon entering the classroom, I leave Maria behind and assume the person of Miriam. I can choose to sit beside a host of legendary figures such as Moses or David, Rachel or Leah. Note-taking becomes a form of dictation. In copying the teacher’s writing on the board, we are practicing some form of composition. Our textbook is full of creatively designed written and oral activities and dialogues, with biblical characters for protagonists. Plenty of aural and oral practice is incorporated and snippets of Holy Scripture are strewn throughout the book.

I experience something similar in my Koine Greek classes, the language into which the Old Testament was translated in the 3rd century B.C., and in which the New Testament was composed. For my teachers, joy, levity, and comedy are essential tools of learning:

‘…the teacher signals that meeting the students is a great joy. This is communicated with nonverbal means, open, positive body language, and profuse use of mostly nonlinguistic sounds, such as laughter, but also certain interjections like ὤ (Oh!) or βαβαί (Wow!). As a light-hearted classroom environment is conducive to learning in many ways, it is desirable that the instructor be not afraid to exaggerate and make use of a comical register that is suitable for this kind of everyday situations.’

[‘Teaching Ancient Greek by the Polis Method’, Michael Kopf & Christophe Rico]

Such practice simply affirms the wisdom of the oldest pedagogical treatise:

μὴ τοίνυν βίᾳ, εἶπον, ὦ ἄριστε, τοὺς παῖδας ἐν τοῖς μαθήμασιν ἀλλὰ παίζοντας τρέφε, ἵνα καὶ μᾶλλον οἷός τ᾽ ᾖς καθορᾶν ἐφ᾽ ὃ ἕκαστος πέφυκεν.

“So, most excellent one,” I said, “don’t raise the children by means of force in the things they learn, but by playing, so you’ll also be able to see what each of them is naturally inclined toward.”

[Republic, Plato 536E-537A, translation by Joe Sachs]

How can this spirit and these techniques possibly be translated into an online environment? Undoubtedly, I have found myself restricted in the amount of TPR (Total Physical Response) I can employ. Nevertheless, I have been encouraged by the extent to which creating and inhabiting a Latin world is possible via the web. It is important to prompt students to think outside the box by asking questions which encourage them to relate to the world beyond our text (we are studying with Familia Romana). I particularly enjoy catching them by surprise and watching their faces light up as they think of a creative way to respond to an unexpected prompt. One such exchange ran as follows:

- Magistra: Quōmodo arbōrēs ornantur vēre? [Teacher: How are the trees decorated in spring?]

- Discipulī: Folia? [Students: Leaves?]

- Magistra: Folia, ita, sed cuius cāsūs? [Teacher: Leaves, yes, but what should be the case?]

- Discipulī: Foliīs, novīs foliīs. [Students: With leaves, with new leaves.]

- Magistra: Recte dīcis! Nunc, dīc totam sententiam. [Teacher: Correct! Now, say the whole sentence.]

- Discipulī: Vēre arbōrēs ornantur novīs foliīs. [Students: In spring the trees are decorated with new leaves.]

- Magistra: Monstrāte mihi folia! [Teacher: Show me some leaves! We had discussed that folium can also mean ‘page’, but several students unexpectedly began to brandish nearby house plants. One student produced a plant in a pot in the shape of a unicorn…]

- Magistra: Fēlīcia, habēsne unicornuum? Discipulī, quōmodo ornātur unicornuus? [Teacher: Joy, do you have a unicorn? Students, how is the unicorn decorated?]

- Discipulī: Unicornuus ornātur foliīs! [Students: The unicorn is decorated with leaves!]

The experience of working through Hans Orberg’s Familia Romana, which is structured as a continuous narrative and written in impeccable classical Latin, is akin to reading a classical text. It serves as a compass for sailing the – sometimes choppy – internet sea. For homework in addition to written exercises, students are asked to listen to recordings of Hans Orberg reading from the text, participate in written discussion forums (colloquia), and record themselves performing dialogues.

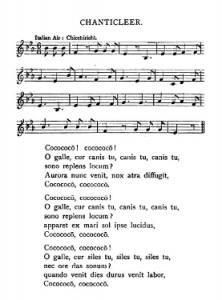

In producing his textbook, Hans Orberg was inspired by English schoolmaster and Cambridge graduate W.H.D. Rouse. Rouse was both an erudite scholar and the inventor of the Direct Method. He prefaces his didactic anthology of songs Chanties in Greek and Latin with a quote from Cicero:

O praeclāram beāte vīvendī et apertam et simplicem et dīrēctam viam.

‘O how splendid, free, simple, and straight is the way of living happily.’ [Cicero, De Finibus, I.57]

In choosing this quote, Rouse draws a parallel between Cicero’s philosophical treatise and the study of ancient languages. By transposing the phrase directam viam (‘straight way’) to the study of language, Rouse coins the title Direct Method. For Rouse, the study of Latin and Greek is most fruitful when brought to life by inhabiting and embodying the languages. His method was not always appreciated by his colleagues: a humorous anecdote relates how a school inspector was less than impressed after happening to drop by Rouse’s classroom in the middle of a joyful – if rather rowdy – re-enactment of the triumph of Caesar (Suet. Julius 49); Rouse brought this episode to life with his song ‘Caesar’s Triumph’ (Chanties in Greek and Latin, p. 83).

[‘Chanticleer’ from Rouse’s Chanties, corresponds with Familia Romana Ch. 14]

I often encounter a false dichotomy between the ‘grammatical approach’ and the Direct Method. It is false for many reasons, not least because in order to speak and write in front of students the teacher must model a robust knowledge of grammar. Another objection is that we can never really know how the Romans spoke. Writing, reciting, conversing, and singing in Latin are very effective didactic tools, employed by grammarians throughout the centuries; these practices do not exist to confute the specialist knowledge of classical scholars. Furthermore, the Direct Method requires that humility be modelled by the teacher, which helps foster a restful classroom atmosphere. In such an environment, students are not afraid to make mistakes; they learn to give and receive correction gracefully and sincerely.

I do not know what that famous English philologist would think of the Direct Method of learning Latin. However, in his seminal essay On Fairy Stories, the phenomenon of joy is mentioned often. Given that inventing a language is essential to the creation of fairy stories (‘one of the highest forms of literature’, – see letter quoted above), we might suppose that he would have approved of a ‘world’ brought into being by the joyful inhabitation of an ancient language.

Bio

Maria Overy first learned to speak Latin when she attended a summer school at the Accademia Vivarium Novum, a college of the humanities where Latin is the only spoken language. She is currently completing an MA in Greek & Biblical Hebrew at the Polis Institute, Jerusalem, a specialist institution for the study of ancient languages in an immersive setting.